By Boniface Keakabetse

The High Court’s dismissal of Wilderness Holdings’ urgent application against Ngamiland Adventure Safaris (NAS) is best understood not merely as a legal setback, but as the latest chapter in a long, shared story rooted in Maun ; a story now entering an inevitable phase of structured separation.

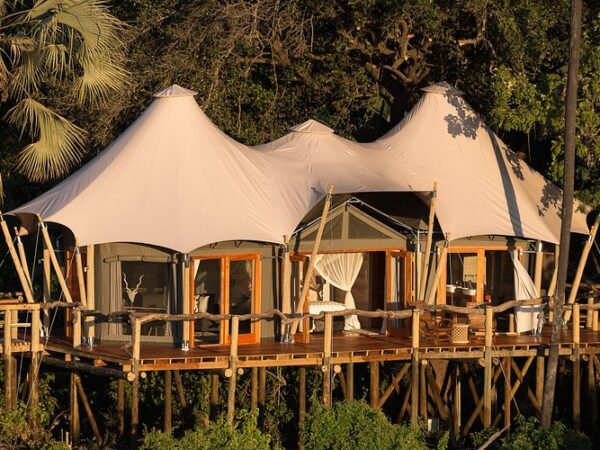

At the centre of the dispute are six high-end safari lodges located in concession NG25 in the Okavango Delta. These properties have long been marketed internationally as Wilderness Jao, Wilderness Tubu Tree, Wilderness Little Tubu, Wilderness Kwetsani, Wilderness Jacana and Wilderness Pelo. While the Wilderness brand has been synonymous with these camps for decades, ownership and on-the-ground management rests with Ngamiland Adventure Safaris.

Both companies are deeply embedded in Maun’s tourism heritage.

Ngamiland Adventure Safaris springs from the multi-generational Kays family, one of Maun’s old families whose presence in Ngamiland and the Okavango Delta stretches back to the late 1800s. Over generations, the family became fully integrated into the Maun community, including initiation into local social structures. This history conferred not only an intimate knowledge of the Delta’s landscapes, but cultural legitimacy ; a deep understanding of customs, community expectations and the delicate balance between land, wildlife and people. NAS’s approach to tourism has always reflected that grounding: rooted in place, continuity and citizen-linked ownership.

Wilderness Safaris, meanwhile, was founded in Maun in 1983, famously beginning with a single Land Rover. From those modest origins, the company went on to become one of the pioneers of modern tourism in Botswana. Over four decades, Wilderness helped define the country’s high-value, low-volume safari model, trained generations of Batswana who now dominate the professional workforce across the safari industry, and set service, conservation and guiding standards that have made Botswana a revered global destination. Its influence has extended beyond camps and guests, shaping industry norms and, arguably, informing tourism policy thinking at a national level.

While Wilderness has since grown into a globally recognised conservation and hospitality brand operating across eight African countries, with corporate headquarters later relocating to Mauritius, Maun has remained a vital logistics, aviation and operational hub for its Botswana business — and the symbolic birthplace of the Wilderness story.

It was from this shared Maun foundation that the partnership between NAS and Wilderness emerged. The arrangement combined local concession control, ownership and cultural knowledge with global marketing reach and international sales expertise. For more than 25 years, Wilderness Holdings, the holding company of the Wilderness Safaris group — marketed and sold bed nights at the NG25 camps, asserting an entrenched exclusive marketing right arising from multiple agreements dating back to 2001 and 2004. Together, the two entities helped build some of the Okavango Delta’s most recognisable and commercially successful safari lodges.

Over time, however, the relationship began to strain.

As Wilderness evolved into a multinational corporate group with diversified offerings across the continent, NAS, which deliberately remained headquartered in Maun , increasingly questioned issues of transparency, reporting, pricing structures and how its camps were positioned within broader, bundled safari products sold globally. The concern was not simply commercial; it went to questions of control, representation and who ultimately shaped the narrative and value of assets rooted in Botswana’s most iconic landscape.

Those concerns culminated on 27 May 2025, when NAS formally notified Wilderness that it was terminating the exclusive marketing agreement. The termination was set to take effect on 1 December 2025, providing seven months’ notice, after which NAS would assume responsibility for its own bookings and sales.

Wilderness responded by seeking urgent court intervention to halt that transition. The High Court’s refusal to grant that relief does not resolve the substantive contractual dispute, which remains before the courts. What it does do is signal judicial reluctance to freeze a commercial relationship that one party has clearly and formally elected to exit, particularly in a sector undergoing structural change.

More broadly, the ruling reflects a wider transition within Botswana’s tourism industry. Locally rooted, citizen-linked enterprises are increasingly seeking greater control over their commercial destinies, even when that means untangling long-standing relationships with powerful international partners that helped build the industry in its formative years.

For Maun, the case carries particular resonance. It is not a story of outsiders challenging locals, nor locals turning against foreign investors. It is a separation between two institutions born in the same town, shaped by the same Delta, but now pursuing different visions of scale, control and future growth.

In that sense, the court ruling is less an ending than a marker ;a signpost pointing to a new phase in Botswana’s tourism economy, where questions of ownership, marketing power and value capture are increasingly being asked not in foreign boardrooms, but here at our home, Maun.